Page 176 - Cyber Terrorism and Extremism as Threat to Critical Infrastructure Protection

P. 176

SECTION II: CYBER TERRORISM AND SECURITY IMPLICATION FOR CRITICAL INFRASTRUCTURE PROTECTION

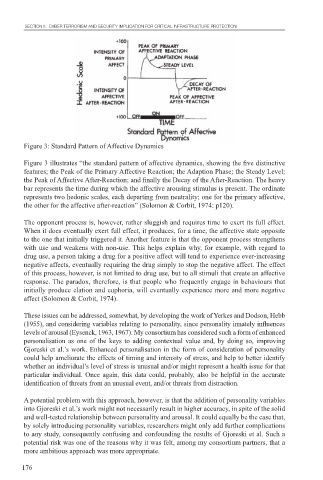

Figure 3: Standard Pattern of Affective Dynamics

Figure 3 illustrates “the standard pattern of affective dynamics, showing the five distinctive

features; the Peak of the Primary Affective Reaction; the Adaption Phase; the Steady Level;

the Peak of Affective After-Reaction; and finally the Decay of the After-Reaction. The heavy

bar represents the time during which the affective arousing stimulus is present. The ordinate

represents two hedonic scales, each departing from neutrality; one for the primary affective,

the other for the affective after-reaction” (Solomon & Corbit, 1974: p120).

The opponent process is, however, rather sluggish and requires time to exert its full effect.

When it does eventually exert full effect, it produces, for a time, the affective state opposite

to the one that initially triggered it. Another feature is that the opponent process strengthens

with use and weakens with non-use. This helps explain why, for example, with regard to

drug use, a person taking a drug for a positive affect will tend to experience ever-increasing

negative affects, eventually requiring the drug simply to stop the negative affect. The effect

of this process, however, is not limited to drug use, but to all stimuli that create an affective

response. The paradox, therefore, is that people who frequently engage in behaviours that

initially produce elation and euphoria, will eventually experience more and more negative

affect (Solomon & Corbit, 1974).

These issues can be addressed, somewhat, by developing the work of Yerkes and Dodson, Hebb

(1955), and considering variables relating to personality, since personality innately influences

levels of arousal (Eysenck, 1963, 1967). My consortium has considered such a form of enhanced

personalisation as one of the keys to adding contextual value and, by doing so, improving

Gjoreski et al.’s work. Enhanced personalisation in the form of consideration of personality

could help ameliorate the effects of timing and intensity of stress, and help to better identify

whether an individual’s level of stress is unusual and/or might represent a health issue for that

particular individual. Once again, this data could, probably, also be helpful in the accurate

identification of threats from an unusual event, and/or threats from distraction.

A potential problem with this approach, however, is that the addition of personality variables

into Gjoreski et al.’s work might not necessarily result in higher accuracy, in spite of the solid

and well-tested relationship between personality and arousal. It could equally be the case that,

by solely introducing personality variables, researchers might only add further complications

to any study, consequently confusing and confounding the results of Gjoreski et al. Such a

potential risk was one of the reasons why it was felt, among my consortium partners, that a

more ambitious approach was more appropriate.

176